“Last year, state lawmakers sought to address concerns about both invasive species and noxious weeds by passing legislation tightening regulations on invasive plants and loosening restrictions on the transportation of noxious weeds.”

“Genetics has essentially been made into a business, with many entrepreneurs and investors battling for a share of this new, innovative money-making venture. Demonstrating a clairvoyance only found in fiction, companies are now advertising laboratory tests that can predict the exact diseases a child might develop in the future.”

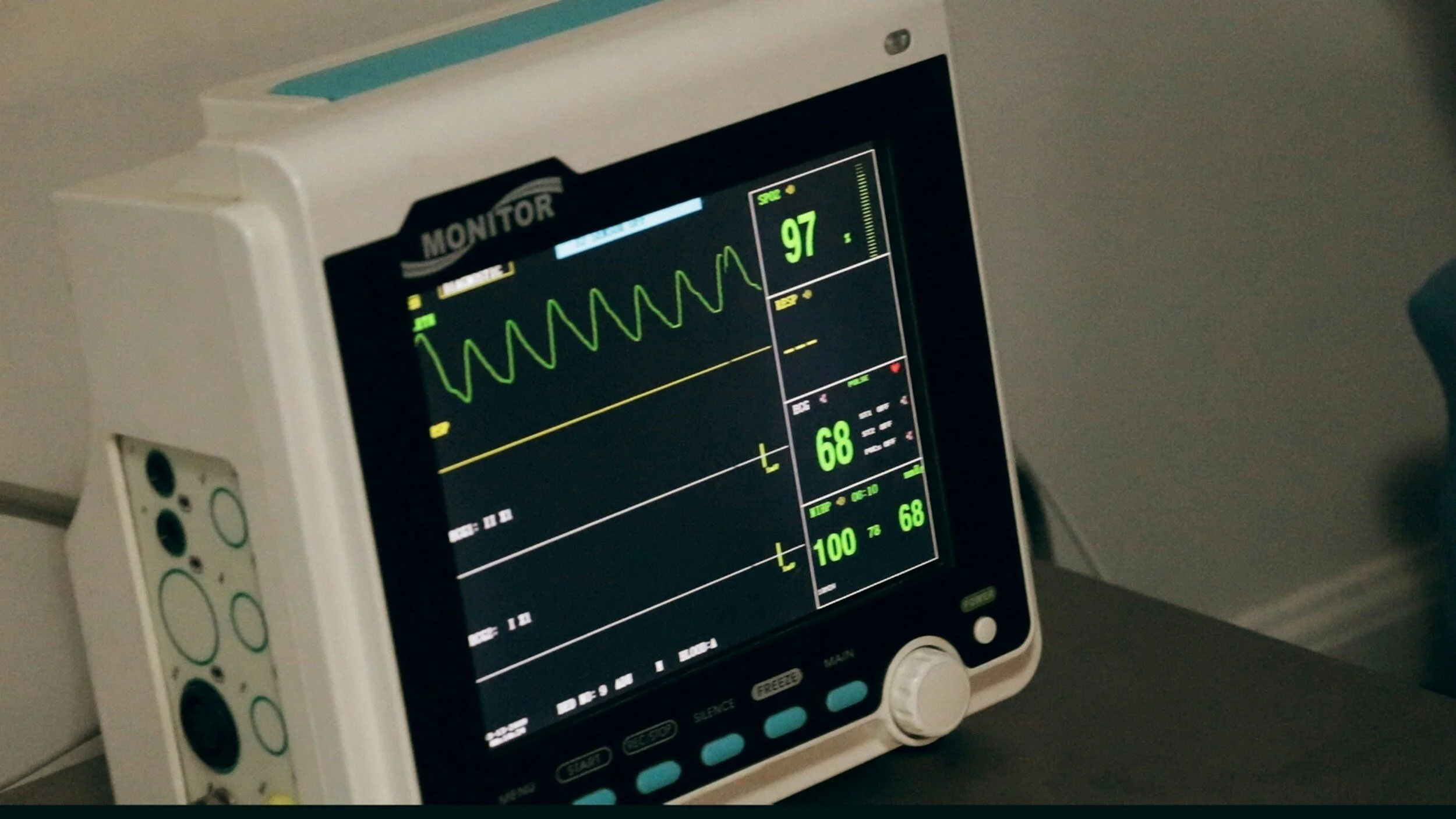

“In both technical and practical ways, there are many scenarios and possibilities to consider before allowing AI to integrate fully into the healthcare field.”

“After decades of uncertainty, a panel of experts at the University of Virginia pronounced climate change to be directly linked with extreme weather events during the virtual Extreme Weather Events & A Changing Environment webinar.”

“Urban heat islands not only endanger human health with their links to heat strokes and heat-related mortality in cities, but they also create a suite of socioeconomic issues pertaining to pollution and energy costs.”

“In an increasingly digitized world, it seems to be emphasized that computerized always means quicker, easier, and better. But in the healthcare setting, current digital systems of health records and vital sign monitoring have many pitfalls that directly sacrifice optimal patient care.”

“The ruling put into question implementation of the clean water act, but EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan assures that the EPA will do “everything we can with our existing authorities and resources to help communities, states, and Tribes protect the clean water upon which we all depend.”

“A quick glance into the UVA dining halls reveals steaming platters of classic foods: chicken, pizza, burgers, salad. Yet upon closer examination, these same meals pile up at the dish return and trash bins as students dispose of their unfinished meals.”

“The anti-LGBTQ+ legislation introduced in recent years is not simply a matter of educational curriculum; it is a matter of the health and livelihoods of millions of United States citizens.”

“Regardless of the potential risks that may come with unshackling prisoners for medical professionals and their caregivers, it does not outweigh the dangerous consequences from the negligence and poor healthcare that these pregnant women may face.”

“Is whole genome sequencing a flawless procedure? No, far from it, and issues regarding cost, privacy, and data analysis are likely not disappearing anytime soon. But with enough time, and as developments in bioinformatics, cost, and public awareness foster, whole genome sequencing is definitely a blueprint that will undergo translation.”

“Surrogacy is no longer a solution for infertility, but a method to adhere to toxic cultural and workplace pressures placed on human and nonhuman beings with childbearing ability.”

“Prenatal testing is a great invention that can help us save many lives and better prepare families for the needs of their unborn fetus, but it can become a more effective service if we begin to prioritize educating families, offer solutions and alternatives rather than passing judgment, and minimize unnecessary testing.“

“As long as healthcare providers are using caution and providing in-depth care, this modern technology should be celebrated, not treated with fear.”

“Physicians should not have to miscode procedures to avoid legal consequences for protecting their patients, and patients should not have to be subject to potential negligence of unknowing hospital staff that endanger their health.“

“The declining caribou populations, as with many prey populations, are due to human activities. Predator management, therefore, may be a last resort, but cannot be justified as a means of benefiting an endangered prey population if it is the sole action taken.“

Billows of black smoke blanket the sky, an enormous and all-consuming dark mass. Barrages of ferocious flames ignite the skyline as fires continue to rage and engulf the remains of the Canadian black spruce trees. Meanwhile, spells of yellow-orange haze descend into the United States causing air quality levels to reach what the Environmental Protection Agency describes as “unhealthy for all” [1]. With air quality-related health issues such as chronic bronchitis and decreased lung function on the horizon, natural disasters such as the Canadian wildfires spark concern about the impact of the environment on our quality of life [2]. The will of nature is out of human hands, yet as environmental disasters pose a health risk to our communities, our civilian duty begs the question: what can we do?

A key distinction to appreciate when contextualizing a natural disaster is to recognize what is and what is not man-made. In the context of wildfires overall, some occur naturally by ignition from the sun’s heat or by a lightning strike. The spread of a wildfire is determined by weather conditions and topography [3]. High temperatures and little rainfall can prime vegetation to fuel the fire to burn faster uphill rather than downhill [4]. These factors are out of human control as wildfires are natural processes. Even though we have the resources to put out these wildfires, sometimes we do not because wildfires are required for the growth and survival of an ecosystem. For example, Yellowstone National Park allows lightning-ignited wildfires to burn because they promote biodiversity as new habitats are generated for differing species and prevent the accumulation of too much leaf litter and deadfall. Controlled fires such as these do not pose a threat to human health, and eventually go out on their own according to the Yellowstone National Park Service [5]. Even Canadian wildfires are common occurrences in the spring and summer as lightning is usually responsible for about half of all fires in Canada as well as 85% of the area burnt each year. However, the other half is where humans must be held accountable [6].

Canada’s record-breaking wildfire season has resulted in culpability being placed on humans who are at fault for this year’s extremities. Some explanations are indisputable such as this year’s early start to wildfire season being the result of unattended campfires and off-road vehicle accidents. One fire in the New Brunswick province began when an all-terrain vehicle caught fire on a trail, igniting the surrounding area [7]. In these situations, the responsibility rests on individuals such as 68% of wildfires between 2017 and 2022 being human-caused in the province of Alberta [8]. Though, this does not explain the full story behind Canada’s historical wildfire season in 2023. [9]. In addition to human error, climate change is a frequently cited cause for several intense weather events, including this year’s Canadian wildfires [10].

Climate change is a man-made, systematic problem, and we must acknowledge how human behavior has contributed to its development. Climate change is exacerbated by the increase in human emissions of heat-trapping greenhouse gasses such as water vapor, carbon dioxide, and methane [11]. On a broader scale, agriculture, oil, and gas operations are major sources of methane emissions that cause the global warming of the earth. Humans are responsible for virtually all of global heating over the last 200 years and as a result of human activity, the last decade was recognized as the warmest on record [12]. In terms of wildfires, climate change can shift factors like temperature, soil moisture, and aridity of forest fuel in favor of more extreme wildfires. For example, increasing temperatures can create conditions of extended drought and persistent heat that can lead to more active and longer wildfire seasons similar to the ones Canada has seen this year [13]. As the climate continues to change, research suggests that the fire season will worsen in coming decades such as parts of Quebec and Ontario will likely see the number and size of wildfires increase [14]. This is a reminder that Canadian wildfires are not a one-time occurrence if we are not proactive in working to combat climate change

Recognizing the role of human action as the reason for the increase in the frequency and severity of natural disasters such as wildfires is important for taking accountability and working towards finding a solution. On an individual basis, the average carbon footprint in the U.S. is about 14.6 tons of CO2, more than double the global average of 6.3 tons [15]. To preserve a livable climate, this number must go down to about 2.0 to 2.5 tons by 2030. The United Nations recommends initiatives such as lowering heating and cooling, using more energy-efficient appliances, making electric rather than gas transportation choices, and eating more vegetables towards reducing emissions [15]. Though, the difficult truth is that it is inconvenient to sacrifice your car to ride the bus at designated times. Making eco-friendly choices, rather than fiscal ones can be a costly downside for consumers [16]. It is also inconvenient to replace every household appliance with renewable energy. By no means, is reducing our carbon footprint an easy task, especially when our change won’t make the impact needed to reverse the overbearing issue of climate change. Regardless, taking individual action still holds great value in influencing our surrounding community, and most importantly, reminding us of our self-worth.

On a global scale, one action may be insignificant, yet the same effort creates a fundamental commitment toward confronting climate change. The dedication to lowering our carbon footprint creates meaning by placing value on the quality of human life including our own. Consider the act of choosing to place a plastic cup in the recycling bin rather than the nearest trash can. For the person waiting to throw their trash away behind you, the moments of thought as you decide which bin to dispose of your items in signifies that individual action does count for something, and possibly, their decision will too. In this instance, recycling contributes towards lowering greenhouse emissions by more than 50% by reducing the energy needed to extract or mine virgin materials [17]. For myself, offering to carpool with my friends or asking them to drive creates meaning by addressing the reality of climate change and how our small group of people can still be part of a movement without sacrificing too much comfort. Carpooling both on the way to work and home can potentially decrease 22%-28% of CO2 emissions, and these numbers remind us that the smallest actions are still relevant contributions in decreasing emissions as they build valuable attitudes around change [18]. These choices are much more than their numerical impact on carbon emissions but are essential in highlighting the importance of individual action under the umbrella of mentality.

Gnawing dread, coursing fear, and racing hearts are some of the unforgettable feelings induced by the sight of orange shrouds above the skies of our homes. The unfortunate reality is that these emotions may become familiar as wildfires are predicted to intensify as a consequence of climate change. While climate change certainly isn’t responsible for every single disaster, it is undeniable the great amount of influence it has on our environment with wildfires being just one example [19]. It is fair to say that without change, the future holds other unpredictable, terrifying moments that could jeopardize the future of humanity. Taking accountability is the first step in the grand scheme of trying to fix our own mistakes. The next is to put the first foot forward in understanding that our personal choices carry a priceless value to individuality and others. Recognizing the importance behind our actions is essential before confronting larger, systematic causes. Collective individual contribution is the effort needed to successfully challenge the companies responsible for the majority of emissions [20]. We all have a part to play, and it has to start with ourselves.

References:

1. Hauser, C., & Moses, C. (2023, July 17). Smoke pollution from Canadian wildfires blankets U.S. cities, again. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/07/17/us/wildfire-smoke-canada-ny-air-quality.html 2. US Department of Commerce, N. (2021, July 2). Why Air Quality is important. National Weather Service. https://www.weather.gov/safety/airquality

3. Moore, A. (2021, December 3). Explainer: How wildfires start and spread. College of Natural Resources News. https://cnr.ncsu.edu/news/2021/12/explainer-how-wildfires-start-and-spread/ 4. Wildfires. Education. (n.d.).

https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/wildfires/#:~:text=Wildfires%20can%20start%20wit h%20a,primed%20to%20fuel%20a%20fire

5. U.S. Department of the Interior. (n.d.). Fire. National Parks Service.

https://www.nps.gov/yell/learn/nature/fire.htm

6. Bilefsky, D., & Austen, I. (2023, June 10). What to know about Canada’s exceptional wildfire season. The New York Times.

https://www.nytimes.com/article/canada-wildfires-what-to-know.html#:~:text=While%20wildfires%20 are%20common%20in,remote%20and%20sparsely%20populated%20areas

7. Owens, B. (2023, June 9). Why are the Canadian wildfires so bad this year?. Nature News. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-023-01902-4

8. 2022 Alberta wildfires seasonal statistics. (n.d.).

https://open.alberta.ca/dataset/db7cdfde-7ccd-4419-989f-09f8bb28da22/resource/afd19465-f0e9-426b -b371-01569145aa86/download/fpt-alberta-wildfire-seasonal-statistics-2022.pdf

9. Livingston, I. (2023, June 16). Analysis | why Canada’s wildfires are extreme and getting worse, in 4 charts. The Washington Post.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/weather/2023/06/12/canada-record-wildfire-season-statistics/

10. Kelly, M. (2023, June 19). What Canadian wildfires signify for climate, Public Health. Dartmouth. https://home.dartmouth.edu/news/2023/06/what-canadian-wildfires-signify-climate-public-health#:~: text=Unlike%20wildfires%20in%20the%20West,to%20global%20warming%2C%20Mankin%20said 11. United Nations. (n.d.-b). What is climate change?. United Nations.

https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change

12. What is your carbon footprint?. The Nature Conservancy. (n.d.).

https://www.nature.org/en-us/get-involved/how-to-help/carbon-footprint-calculator/ 13. Wildfires and climate change. Center for Climate and Energy Solutions. (2023, July 14). https://www.c2es.org/content/wildfires-and-climate-change/

14. Wang, X., Swystun, T., & Flannigan, M. D. (2022). Future wildfire extent and frequency determined by the longest fire-conducive weather spell. Science of The Total Environment, 830, 154752. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154752

15. United Nations. (n.d.-a). Actions for a healthy planet. United Nations.

https://www.un.org/en/actnow/ten-actions#:~:text=Eating%20more%20vegetables%2C%20fruits%2C %20whole,energy%2C%20land%2C%20and%20water

16. Ofei, M. (2023, May 25). Why sustainable products are more expensive (and how to save money). The Minimalist Vegan.

https://theminimalistvegan.com/why-are-sustainable-products-expensive/#:~:text=So%20yes%2C%20s ustainable%20products%20are,the%20cost%20of%20going%20green

17. Climate change, recycling and waste prevention. Climate change, recycling and waste prevention from King County’s Solid Waste Division - King County. (n.d.).

https://kingcounty.gov/depts/dnrp/solid-waste/programs/climate/climate-change-recycling.aspx#:~:tex t=Recycling%20helps%20reduce%20greenhouse%20gas,extracting%20or%20mining%20virgin%20mate rials

18. Bruck, B. P., Incerti, V., Iori, M., & Vignoli, M. (2017). Minimizing CO2 emissions in a practical daily carpooling problem. Computers & Operations Research, 81, 40–50.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cor.2016.12.003

19. Environmental Protection Agency. (n.d.). Climate Change Indicators: Weather and Climate. EPA. https://www.epa.gov/climate-indicators/weather-climate#:~:text=Rising%20global%20average%20tem perature%20is,with%20human%2Dinduced%20climate%20change.

20. Ekwurzel, B., Boneham, J., Dalton, M. W., Heede, R., Mera, R. J., Allen, M. R., & Frumhoff, P. C. (2017). The rise in global atmospheric CO2, surface temperature, and sea level from emissions traced to major carbon producers. Climatic Change, 144(4), 579–590.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-017-1978-0

Many of us have encountered a friend who shares a “medical hack” when they reference that distant family member –– an uncle or a cousin –– who can prescribe them whichever medication they choose. That friend may rant or rave that whenever they are sick, “amoxicillin” or any sort of antibiotic is their panacea which cures even the most stringent of colds. However, I do not utilize the word colds lightly as that is a viral infection and many times, these medications are not utilized with the backing of the rigorous diagnostic process that a clinician performs as part of patient care. Rx has now effectively become through the family tree; instead of having the protective gutter guards that prevent one from unnecessarily taking medication, access has been expanded. This has both beneficial and detrimental impact on patient care and therefore has serious ethical implications. These implications cannot be understood without laying a simple foundation: who in the medical system is eligible to prescribe and can be deemed a “prescriber,” and what legislative stipulations and ethical obligations govern that ability? Furthermore, with the understanding of prescriptive authority, an ethical scenario, and then some legislative context, one can understand that the ethical guidelines that have been established are clear, but need additional reinforcements.

Prescriptive authority is an area of healthcare that has seen accelerated changes within recent years through the growth of physician assistants (PAs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) which have a scope of practice that has expanded and evolved over time [1]. Physicians with the highest degree of prescriptive authority are those with a Doctor of Medicine (MD) or a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) designation as they are able to prescribe medications, including controlled substances which include medications such as opioids, stimulants, depressants, hallucinogens, and anabolic steroids [1]. Furthermore, with a Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) license, these physicians are able to prescribe Schedule II to V medications, which are narcotics and controlled substances. The advent of the first physician assistants class formed in 1965 saw the advent of a novel healthcare professional seeking to fill the gap left by the shortage of physicians. Although state law varies, these healthcare professionals lack complete autonomy as they must be overseen by a physician. Furthermore, the advent of nurse practitioners were seen to deal with the lack of access to pediatric care [1]. Unlike PAs, NPs have greater prescriptive privileges in many states and do not require physician supervision as they are even allowed to prescribe controlled substances. With the increase in PA and NP professionals in recent years, the progressive increase in prescriptive authority has led to changing state laws to increase their autonomy in order to improve healthcare accessibility [1].

Having established those who are able to prescribe medication, diving into a simple ethical scenario is foundational for understanding the ethics of family pharmacists –– if your spouse or partner got a skin infection and needed an antibiotic, is it ethical for you to prescribe that medication to them [2]? There are serious ethical implications and under certain circumstances, it can be argued that it is ethically permissible to treat one’s family members, but in other situations it is not appropriate. Defining the ethical boundary here is incredibly important as it will come with context and provides a framework for caregivers. In emergency situations, such as a cardiopulmonary resuscitation, it is clear that a physician should treat their immediate family member without question as the emergency situation would require them to act to save a life [2]. However, this is not the situation that most ethical concerns would arise; those matters occur when symptoms are nonemergent, when a disease is out of the scope of one’s clinical skills allowing for improper diagnosis.

The Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs of the American Medical Association determined that if the condition is only a short-term and minor problem, such as a skin infection, it is permissible for a physician to treat family members. The ethical boundary here is that the condition must be short-term, whereas long-term treatments are not permissible [3]. Furthermore, in their analysis of 400 medical staff physicians, they found that 99% of physicians had received requests from family members for medical advice or therapy with 83% of respondents reporting that they had prescribed medication for a family member, and 72% reporting that they had conducted a physical examination. This evidence shows that physicians are utilized by their families as sources of “discounted” medical care. The serious implication and problem with treating family members is the potential for personal relationships to impact treatment and determination of the optimal course of therapy for a patient to undergo [2]. In Drs. Korenman and Mramstedt’s article published in the The Western Journal of Medicine, they argued that several conditions must be met for physicians to prescribe to family members: the ailment is within the physician’s expertise, the physician should not accept any limitations on access to patient’s medical records, physicians should know enough about the method of therapy to feel comfortable with it suse, and follow-up is essential for the treatment to be successful.

These guidelines are solid, but they do not provide enough specificity into the core issue of family pharmacists –– the implication that prescriptions can be made for unnecessary or improperly used medication [4]. In some states, it is completely illegal and rightfully so for physicians to prescribe controlled substances to themselves or other immediately family members, such as North Carolina Rules 21 NCAC 32 B.1001, 32S.0212, and 32M.0109; however, the prescription medications are still legal to be prescribed to family members [5]. Many of these prescriptions can be made for patients who are receiving treatment for conditions they may not have been properly diagnosed. For instance, the friend who has a viral infection or a cold but claims that azithromycin is a panacea for all of their problems. A family member may give them an “Rx” for this medication to treat a condition which it will not even remotely improve and as a result, that patient who is effectively self-prescribing is causing greater damage and the potential generation of antibiotic resistant bacteria [6].

The ethics here are clear, but the legislation is not legally binding enough. The ethical scenarios essentially establish that patients must be in non-life threatening scenarios within a physician’s scope of reference and to where all diagnostic ability can be used. These situations are often not the contexts in which these physicians are prescribing medications, and many times these guidelines established by the American Medical Association are not adhered to [7]. The ethics here are clear, but the legislation fails to protect patients, even when they believe that a family member could be protecting them.

Greater legislative constraints must be placed on “family pharmacists.” That is where there are largely restrictions on “controlled substances” for prescribers, many other prescription medications can have harmful effects beyond just addiction which is the reason for the controlled element of many of these medications [8]. Furthermore, there needs to be some legal protection in place for physicians. In order to prescribe to family members, they must go through higher levels of approval, such as an ethics board where documentation of treating immediate friends and family members can be reviewed following treatment. The proposed regulatory process is not a slowing down of treatment, but that all of the diagnostic processes with a justification of the treatment plan must be defended under an annual review. Failure to disclose these treatments should potentially result in loss of licensure.

This may potentially seem strict and stringent to many, but I feel that given the history of the opioid epidemic and the potential negative effects of unmitigated family pharmacies that there must be additional safeguards in place. The system that I have proposed is online, the specificity of it is broad, but its intention is multi-pronged: regulate family pharmacies, protect patients, and maintain efficiency. I do not want this potential legislative action to hinder the ability of patients to receive care, but there must be a higher level of scrutiny placed upon these situations in order to guarantee that physicians are marking ethical and accurate decisions as bias is inherent in these treatment plans. I believe that the access to medicine provided through these close connections to providers can be of great benefit to patients, but that does not mean that it cannot also be of great harm. To mitigate and minimize this harm is an obligation on part of governments who are aware of these backdoor prescriptions.

Sources:

1) Zhang P, Patel P. Practitioners And Prescriptive Authority. [Updated 2022 Sep 19]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574557/

2) Korenman, S. G., & Bramstedt, K. A. (2000). Your spouse/partner gets a skin infection and needs antibiotics: is it ethical for you to prescribe for them? Yes: it is ethical to treat short-term, minor problems. The Western journal of medicine, 173(6), 364. https://doi.org/10.1136/ewjm.173.6.364

3) La Puma J, Stocking CB, La Voie D, Darling CA. When physicians treat their own families: practices in a community hospital. N Engl J Med 1991;325: 1290-1294.

4) Latessa, R., & Ray, L. (2005). Should you treat yourself, family or friends?. Family practice management, 12(3), 41–44.

5) Resources & Information. 2.2.3: Self-Treatment and Treatment of Family Members. (n.d.). https://www.ncmedboard.org/resources-information/professional-resources/laws-rules-position-statements/position-statements/self-treatment_and_treatment_of_family_members

6) What happens when you write rx’s for relatives | mdlinx. (n.d.). https://www.mdlinx.com/article/what-happens-when-you-write-rx-s-for-relatives/lfc-3094

7) Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(5):396-397. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2012.14.5.coet1-1205.

8) The controlled substances act. DEA. (n.d.). https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/csa

The ambiguous mystery of consciousness that relates our subjective phenomenal experiences to an objective reality has puzzled the human mind since antiquity. From as early as the ancient Greeks to the 21stcentury, the concept of consciousness has generated numerous inquiries and theoretical propositions in the divergent fields of philosophy and neuroscience [1]. Alas, the concept of consciousness is ill-defined across time and culture given the juxtaposing nature of the term in both the metaphysical and scientific sense. In the philosophical text A Treatise of Human Nature, the Scottish philosopher David Hume described consciousness as “nothing but a bundle or collection of different perceptions, which succeed each other with an inconceivable rapidity, and are in perpetual flux and movement” [2]. In his psychoanalytic theory, the Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung characterized consciousness as “the function or activity which maintains the relation of psychic contents to the ego” [3]. The French cognitive neuroscientist Stanislas Dehaene explained consciousness in his Global Neuronal Workspace Theory as a “global information broadcasting within the cortex [that] arises from a neuronal network whose raison d’être is the massive sharing of pertinent information throughout the brain” [1, 4]. These definitions, among many others, are nevertheless insufficient to explain consciousness if isolated on their own unless they are synthesized into a continuum of interwoven ideas that can account for the heterogeneous nature of consciousness [1].

Despite the dispute among historical and contemporary thinkers on the questions of consciousness and its neural correlates, the essence of each and every argument is fundamentally rooted in either the “easy” or “hard” problems of consciousness, as formulated by the Australian philosopher David Chalmers [5]. The “easy” problem seeks to identify mechanistic explanations for the various cognitive phenomena (e.g., perception, learning, behavior) resulting from the underlying biophysical processes of the brain. On the other hand, the “hard” problem accounts for why there is an association between such phenomena and consciousness [6]. However, the objective of the discussion herein is not to individually distinguish and comprehensively assess the myriad theories of consciousness. Instead, the concept of consciousness and its distinguishing features are considered in the context of clinical patients who suffer from disorders of consciousness (DOC), in which altered levels of consciousness has presented a neuroethical challenge in evaluating the life and death of DOC patients, particularly when aspects of their inherently intrinsic values are pathologically compromised to render them in a state of extreme vulnerability [7].

In the clinical context, consciousness is precisely conceptualized according to the Aristotelian formulation of wakefulness and awareness, wherein the state of consciousness is evaluated on the basis of arousal (e.g., eye-opening) and the ability to react to external stimuli (e.g., visual tracking), respectively [1]. Specifically, the elements of wakefulness and awareness encapsulate the ensuing features as the core indicators of consciousness: distinct sensory modalities, spatiotemporal framing, intentionality, dynamicism, short-term stabilization, and an integration of all components of the conscious experience [8]. The extent of the two said elements, however, varies according to the neurophysiological conditions of the DOC patient, which factors in variables such as brainstem reflexes, functional communication, language, and fMRI/EEG evidence of association cortex responses. Depending on the results of these testing variables that relies on the use of dichotomic binary communication paradigms (i.e., yes/no or on/off), the patients’ condition can thus be diagnosed, which includes, inter alia, coma, persistent vegetative state (PVS), unresponsive wakefulness syndrome (UWS), minimally conscious state (MCS), post-traumatic confusional state (PTCS), covert cortical processing (CCP), and locked-in syndrome (LIS) [1].

To begin the discussion on the neuroethics of patients with DOC, the controversial case of Terri Schiavo and her legacy ought to be taken into reflection [9]. In 1990, Schiavo was left in a vegetative state after suffering from a cardiac arrest, a symptom of hypokalemia induced by her eating disorder. From that point onward, Schiavo was in an eye-open state but was unaware of herself and her environment (a dissociation of awareness from wakefulness) for the next 15 years of her life until her death in 2005. Schiavo’s neurologist initially concluded that her condition was irreversible and that she was no longer capable of having emotions, which caused her spouse to request the removal of her feeding tube and any life-sustaining treatment. Schiavo’s parents were diametrically opposed to this decision because they held onto the belief that there was a possibility for neurological recovery and that Schiavo was still a sentient being. Both parties claimed to act in Schiavo’s best interest as the justified surrogate decision-maker, yet their familial conflict had ultimately gone to litigation, in which the verdict ruled in favor of Schiavo’s spouse. Upon close examination, the tragic outcomes of Schiavo’s case underscores several ethical violations in the medical, legal, and social realms in relation to end-of-life decision-making and the exercise of autonomy.

Recent developments in functional neuroimaging and neuroelectrophysiological methods have changed the ways through which DOC patients are diagnosed, prognosed, and treated. The most prominent revelation from such advancement is the high rates of misdiagnosis and inaccurate prognostication among DOC patients by clinicians, wherein cases of patients who are originally diagnosed as PVS are in reality reclassified as MCS upon neuroimaging procedures. In contrast to PVS patients, MCS patients are found to display both wakefulness and behavioral signs of rudimentary awareness. Ultimately, such misdiagnosis can be attributed to several factors such as sensorimotor impairments in the patient, or confirmation bias in the clinician. In turn, this creates epistemic risks because of limited certainty in DOC nosology [1]. Notwithstanding the promising potential of neuroimaging and similar neurotechnologies (e.g., brain-computer interfaces), the medical practice of neuroimaging itself poses an increasing degree of ethical tension due to the lack of informed consent from the DOC patient themselves as a requirement prior to undergoing neuroimaging. This is a challenge that is often highlighted in neuroimaging-driven DOC research, compounded with the disclosure of experimental results to the patient themselves or their family, which are deemed as imperative to mitigate miscommunications in patient-clinician relationships [10, 11].

Given that cognitive biases are a salient class of factors contributing to misdiagnoses in DOC, emphasis ought to be placed on the prevalence of ableist bias in influencing erroneous, monotonic judgments with respect to the neurological outcomes of DOC patients. Note that this particular issue is a byproduct of the disability paradox—a phenomenon that occurs when individuals with disabilities claim to experience a good quality of life despite the fact that many external observers perceive them as in a state of suffering [12]. As a result, prejudiced assumptions create a discrepancy between the actual wishes of the DOC patient and what others perceive as acceptable; oftentimes, the latter revolves around the belief that being in an unconscious state is worse than death [13]. Though in the event that the preference of the DOC patient is well-documented in regard to the best course of action to take when the patient is nonverbal or behaviorally disabled, the judgment of the clinician will not be a matter of importance. A study by Patrick et al., however, discovered that there exists a psychological discordance among DOC patients in which patients who initially expressed the belief that life is not worth living in such conditions still wished to undergo life-sustaining interventions. Hence, the implications of the ableist notion that “it is better to be dead than disabled” is not meant to be taken in the literal sense [14]. Fortunately, functional neuroimaging is indeed capable of unveiling residual consciousness and psychological continuity even if the apparent behavioral characteristics of the DOC patient suggests otherwise, as shown in a neuroimaging study by Owen et al. [15]. This scenario presents the common ethical problem in regard to the premature or uncertain termination of life-sustaining care for DOC patients based on the decision of moral agents such as a surrogate (e.g., the patient’s kin) or a third party (e.g., government), which may be ill-informed or morally absolutist at times [16].

Thus, upon careful consideration of such scenarios and the case of Schiavo, is it still morally permissible to withdraw artificial life support from DOC patients in the absence of informed consent or advance directives from the will of the patient themselves? While it is reasonable to argue that it is futile to continue maintaining the life of DOC patients given the lack of expected utility, this justification is heavily rooted in a deep sense of therapeutic nihilism—an aporetic belief toward the successful curing of a disease—that gave rise to a pessimistic outlook on the assessment of predicting the likelihood of meaningful recovery among DOC patients and their right to life-sustaining treatment from the view of clinicians. [13]. Evidently, with the patients’ best interest at stake, the ways through which patient outcomes are perceived under the lens of undue pessimism coupled with a saturated sense of self-fulfilling prophecy illustrate the negligence of DOC patients’ potential to recover and regain functional independence in the long-run. After all, behavioral recovery typically occurs beyond the minimum standard timeframe of 28 days during post-brain injury, as suggested in an observational study conducted by Giacino et al. on DOC patients with PVS/MCS [17]. Such empirical evidence, therefore, rejects the futility thesis in DOC care and underscores the risk of superimposing the beliefs and values of the observers onto the patient. Integrating prudence and fiduciary responsibility into the ethos of palliative care for DOC patients are thus relevant in the clear discernment of consciousness from the nonconscious state [1].

In recognizing the effects of pessimistic attitudes on clinical decision-making, the consequentialist argument of cost and health utilities in treating DOC patients is another antithetical statement toward preserving the life of DOC patients. Indeed, in some outlying cases, extensive care for patients with DOC may not necessarily result in favorable outcomes, irrespective of the duration and intensity of the treatments that are provided. In such circumstances, the harm-benefit analysis yielded problems such as significant emotional distress and financial losses for the families of DOC patients, as well as failing to protect the dignity and comfort of DOC patients as a consequence of undergoing continuous painful treatments that may seem to have minimal benefits, compounded with the fact that these resources are scarce in most instances. Additional opportunity costs that may incur on the families of DOC patients include renouncing education or employment opportunities to act as caregivers for their beloved [1]. Hence, the continuation of sustaining the life of DOC patients under such criteria cannot possibly maximize the cost and health utilities of the patient and their family.

To balance these potential harms, however, it ought to be noted that the proclivity for utility maximization is in conflict with the contractual obligation of the clinician in improving the care of DOC patients without resorting to abandonment and risk aversion and guaranteeing them the value of human life. The life of a human being and the act of protecting its existential stature is what translates to having dignity in lieu of death, such that the phrase “dying with dignity” has been diluted in meaning and is contradictory in this interpretation of dignity [14, 15]. Furthermore, to withhold distributive justice in the clinical setting to align with democratic principles, resources ought to be allocated in a fair, unbiased manner to ensure equity in access to appropriate treatments for DOC patients that are also affordable for all to offset the inclination among clinicians to allocate rehabilitative resources to patients with a higher chance of recovery than those with a poor course of prognosis [13]. Therefore, it is a necessary risk to provide life-sustaining treatment even to DOC patients with a low likelihood of recovery and survival, for doing so will lead to further advancements in improving DOC care and make medical progress in overcoming technical limitations and understanding the complexity of DOC for posterity.

On the subject of personhood, however, many observers who are under the influence of therapeutic nihilism tend to perceive DOC patients as an empty vessel that is devoid of personhood given their loss of cognitive capacities, which are claimed to be indispensable for consciousness to be constituted. Such perceptions are merely natural considering the hypercognitive nature of postmodern Western societies and cultures, wherein the deprivation of certain capacities that the majority deems as important has separated those who are unworthy of care and attention from those who are worthy. Nevertheless, regardless of whether or not personhood is ascribed to patients with DOC, the worth of a human life should not be evaluated on the basis of the unlikeness of the human mind, for all persons ought to be respected in the name of equality and solidarity as fundamental moral sentiments to maintain a just legal and healthcare system, especially toward those who are in their most vulnerable state [14, 18].

A reinforcing assertion on defending the continual existence of personhood claims that consciousness is not an essential prerequisite for the acknowledgement of one’s identity, hence the intrinsic values of DOC patients are retained to qualify them as individual persons in spite of their incompetence to communicate or act in accordance with their freedom of will [19]. Even more so, the implementation of disability rights perspectives into the social analysis and lawful policymaking surrounding DOC patients proclaims that individual identities are not singularly characterized by working cognitions and emotions. As opposed to basing the identity of DOC patients on their medical conditions, their identity is constructed around the notion that their disabling attributes as a result of DOC is an inalienable component of their overall identity. Indeed, disability is only transparent when life-sustaining treatments are denied to DOC patients as a reflection of the institutional failure to both accommodate those who are in urgent need of care and withhold constitutional and federal civil rights protections, specifically in regard to the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) that ought to be applied universally [20, 21, 22].

Even in the depths of inescapable nihilism in managing DOC care, ethics must prevail in remembrance of the principle of in dubio pro vita—"when in doubt, favor life” [23]. In considering the complex diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties in conjunction with uncertain prognostications for patients with DOC, the health prospects of the patient are at a constant risk due to the epistemological interstice between current understandings of consciousness and the behavioral conditions of DOC patients [10]. Therefore, to overcome the existing state of DOC care that is characterized by issues of informed consent, cognitive biases, futility-inspired pessimism, unjust resource allocations, negligence of personhood, and various unknown risk factors, it demands the deployment of effective medical and legal protocols and ethical guidelines for pragmatic clinical decision-making. As such, the traditional beliefs in the practices of medicine and law must be challenged to preserve the life of DOC patients alongside their personal identity, dignity, freedom of will, and most crucially, the right to live at the heart of humanity.

References

1. Young, M. J., Bodien, Y. G., Giacino, J. T., Fins, J. J., Truog, R. D., Hochberg, L. R., & Edlow, B. L. (2021). The neuroethics of disorders of consciousness: a brief history of evolving ideas. Brain, 144(11), 3291-3310.

2. Hume, D. (2009). A treatise of human nature. (P.H. Nidditch, Ed.). Clarendon Press. (Original work published 1739-40)

3. Jung, C. G. (1921). Psychological Types. In Collected Works (Vol. 6). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

4. Mashour, G. A., Roelfsema, P., Changeux, J. P., & Dehaene, S. (2020). Conscious processing and the global neuronal workspace hypothesis. Neuron, 105(5), 776-798.

5. Chalmers, D. J. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of consciousness studies, 2(3), 200-219.

6. Mills, F. B. (1998). The easy and hard problems of consciousness: A Cartesian perspective. The Journal of mind and behavior, 119-140.

7. Roskies, A. (2021, March 3). Neuroethics. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved January 8, 2023, from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/neuroethics/ 8. Farisco, M., Pennartz, C., Annen, J., Cecconi, B., & Evers, K. (2022). Indicators and criteria of consciousness: ethical implications for the care of behaviourally unresponsive patients. BMC Medical Ethics, 23(1), 30.

9. Weijer, C. (2005). A death in the family: reflections on the Terri Schiavo case. CMAJ, 172(9), 1197-1198.

10. Young, M. J., Bodien, Y. G., & Edlow, B. L. (2022). Ethical considerations in clinical trials for disorders of consciousness. Brain Sciences, 12(2), 211. 11. Istace, T. (2022). Empowering the voiceless: disorders of consciousness, neuroimaging and supported decision-making. Frontiers in psychiatry/Frontiers Research Foundation (Lausanne, Switzerland)-Lausanne, 2010, currens, 13, 1-10. 12. Albrecht, G. L., & Devlieger, P. J. (1999). The disability paradox: high quality of life against all odds. Social science & medicine, 48(8), 977-988.

13. Choi, W. (2022). Against Futility Judgments for Patients with Prolonged Disorders of Consciousness.

14. Golan, O. G., & Marcus, E. L. (2012). Should we provide life-sustaining treatments to patients with permanent loss of cognitive capacities?. Rambam Maimonides Medical Journal, 3(3).

15. Owen, A. M., Coleman, M. R., Boly, M., Davis, M. H., Laureys, S., & Pickard, J. D. (2006). Detecting awareness in the vegetative state. science, 313(5792), 1402-1402.

16. Fins, J. J. (2005). Clinical pragmatism and the care of brain damaged patients: toward a palliative neuroethics for disorders of consciousness. Progress in brain research, 150, 565-582.

17. Giacino, J. T., Sherer, M., Christoforou, A., Maurer-Karattup, P., Hammond, F. M., Long, D., & Bagiella, E. (2020). Behavioral recovery and early decision making in patients with prolonged disturbance in consciousness after traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurotrauma, 37(2), 357-365.

18. Post, S. G. (2000). The moral challenge of Alzheimer disease: Ethical issues from diagnosis to dying. JHU Press.

19. Foster, C. (2019). It is never lawful or ethical to withdraw life-sustaining treatment from patients with prolonged disorders of consciousness. Journal of Medical Ethics, 45(4), 265-270.

20. Forber-Pratt, A. J., Lyew, D. A., Mueller, C., & Samples, L. B. (2017). Disability identity development: A systematic review of the literature. Rehabilitation psychology, 62(2), 198.

21. Rissman, L., & Paquette, E. T. (2020). Ethical and legal considerations related to disorders of consciousness. Current opinion in pediatrics, 32(6), 765. 22. Chua, H. M. H. (2020). Revisiting the Vegetative State: A Disability Rights Law Analysis.

23. Pavlovic, D., Lehmann, C., & Wendt, M. (2009). For an indeterministic ethics. The emptiness of the rule in dubio pro vita and life cessation decisions. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 4(1), 1-5.

As an emerging neuromodulation tool, optogenetics affords the capability of manipulating neuronal activities of genetically defined neurons using light. In principle, optogenetics offers scientific insights into deciphering the complexity of various behavioral states and the neural pathways that underpin normal and abnormal brain functions with therapeutic applications [1]. In fact, human clinical trials have been initiated in utilizing optogenetics to treat retinitis pigmentosa to restore vision, and animal models have been extensively used in optogenetics studies to develop therapies for a myriad of nervous system disorders as an alternative to deep brain stimulation (DBS) [2]. To understand the inner workings of this novel neurotechnology, the basic neurobiological basis of synaptic communication between neurons must be briefly elaborated. Fundamentally, Na+ions flow into neurons until the threshold potential is reached with sufficient voltage to elicit an action potential along the axons of successive depolarized neurons to transmit information by means of neurotransmitter release at the synapses. For ions to passively travel into the neurons across the cell membrane for activation or deactivation requires the gated ion channels to be opened or closed, respectively, which can be done by applying an external stimulus such as temperature and ligand molecules. Alternatively, protein pumps can also facilitate the inward flow of specific ions via active transport under similar stressors. Neurons eventually become hyperpolarized as K+ions begin to flow outward to inhibit the signal until the threshold is reached again from the resting potential, all of which are done iteratively [3].

The discovery of optogenetics has thus introduced light-gated channels and pumps as a new mechanism for controlling synaptic communication among neurons. Light-sensitive proteins called opsins are the genes responsible for encoding light-gated channels and pumps, which are typically found in microbial species of archaea, bacteria, and fungi—the source from which Type I opsin genes are derived [1]. Opsins are subsequently cloned to be expressed in a target population of neurons that lack light-gated channels and pumps via viral vectors (i.e., adeno-associated viruses (AAV) or lentiviruses (LV)), thereby enabling the control and regulation of neuronal activities of various neural circuits at the supramacroscopic scale in real time with light through the insertion of an optical fiber. Upon the illumination of light, neurons can either be excited or inhibited, depending on the nature of the optogenetic proteins that are neuronally expressed in accordance with the functions that the researcher intends to mediate for individual neurons [2]. Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) is a light-gated cation channel protein that can excite neurons when illuminated with blue light at regular pulses, which causes the inward flow of cations (e.g., Na+, Ca2+, H+) to increase the rate of action potentials [4]. To inhibit the activity of neurons, the yellow-light sensitive proton pump archaerhodopsin-3 (AR3) is used, wherein protons are transported out of neurons to decrease the rate of action potentials. Similarly, wild-type halorhodopsin (NpHR) is a Cl ion pump that also engages in neuronal inhibition in response to the continuous illumination of yellow light to sustain neurons in a hyperpolarized state [5].

Given the bidirectional modality of optogenetics in controlling specific neuronal ensembles by means of regulating the movement of ions to facilitate or prevent synaptic communication, one application of optogenetics extends to its potential for modifying memories as a form of improved and versatile memory modification technology (MMT). Pre-existing MMTs include DBS along with pharmacological agents (i.e., propranolol or mifepristone), all of which can alter the brain via external means. However, due to the indiscriminate spread of electrical currents to neighboring nerve fibers of targeted cells in DBS and the poor temporal precision in the administration of pharmacological agents, optogenetics are fortunately capable of compensating these practical limitations [6]. The spatiotemporal selectivity and precision of optogenetics are best illustrated when considering the diversity of light-sensitive proteins that can be expressed in correspondence to the different cell types in the central nervous system (CNS), some of which are genetically defined such that they are restricted to limited optogenetic proteins based on the type of neurotransmitters they secrete or the direction of their axonal projections [2].

Therefore, optogenetics renders the ability for memory modification in such a manner that specific memories, whether they are newly formed or well-consolidated, can be activated or deactivated in their respective engrams by manipulating the activities of targeted neurons in the hippocampal region of the brain, primarily at the dentate gyrus (DG) where memories are initially formed from the merging of sensory modalities [7, 8]. For example, Liu et al. has demonstrated the implantation of de novo false memories into mice through optogenetic manipulation using ChR2 aided by contextual fear conditioning [9]. Another memory modification experiment using optogenetics conducted by Guskjolen et al. has surprisingly shown that lost, inaccessible memories in infant mice due to infantile amnesia can be recovered by optogenetically targeting hippocampal and cortical neurons responsible for encoding infant memories, ensued by reactivating the ChR2-labeled neuronal ensembles when the infant mice reached adulthood after a period of three months [10].

Additional applications of optogenetics in the context of memory modification includes enhancing the cognitive capacity for memory, changing the valence of a memory (from negative to positive, and vice versa) without distorting the content, and treating memory impairments that are characteristic of conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in clinical patients [6]. Notwithstanding the futuristic promise of optogenetics, the apparent harm of manipulating select memories in humans to various extents on demand is of equal relevance when considering the collective ramifications of this novel yet ambivalent neurotechnology. The neuroethical flaws of using optogenetics for memory modification are thus worthy of being discussed in detail.

Of similar nature to many revolutionary technologies such as the CRISPR/Cas9 system for genome editing, safety risks present a limitation to the use of optogenetics for memory modification applications given its invasive nature—requiring the injection of viral vectors into the brains of experimental subjects for the in vivo delivery of optogenetic proteins [11]. Furthermore, deep brain optogenetic photostimulation also requires tethered optical fibers or other forms of implants to be surgically inserted into the brain to provide a light source, which may cause tissue damage, ischemia, and infections as with many invasive neurosurgeries [12]. A non-invasive approach in the utilization of optogenetics, interestingly, has been developed by Lin et al. using an engineered red-shifted variant of ChR known as red-activable ChR (ReaChR) that was expressed in the vibrissa motor cortex of mice. With the penetration of red light through the external auditory canal, neurons can subsequently be optically activated to drive spiking and vibrissa motion in mice to enable transcranial optogenetic excitations with an intact skull [13].

Nevertheless, safety risks cannot be easily dismissed in a premature manner in the event that optogenetic manipulations lead to off-target behavioral or emotional effects, wherein unpredictable network changes may occur in areas outside of the targeted optogenetic activation or deactivation zone [14]. For example, episodic memories are not solely distributed in the hippocampus; the entire system also consists of surrounding brain structures of the medial temporal lobe including the perirhinal and entorhinal cortices in conjunction with structurally connected sites (e.g., thalamic nuclei, mammillary bodies, retrosplenial cortex). Targeting a set of hippocampal neurons that is known to encode a specific memory may also induce unforeseeable changes, for it is presumed that their function is not solely exclusive to memory encoding. Moreover, since the off-target effects pertaining to the optogenetic modification of memory have not been heavily analyzed in the neuroethical literature, it adds the weight of uncertainties regarding safety issues. The level of uncertainties is further elevated by the risk of long-term expression of optogenetic proteins in the mammalian brain with unknown consequences [6].

Beyond safety issues and technical limitations of optogenetics, attention is now shifted toward issues unique to optogenetics that may or may not be shared among pre-existing MMTs in the context of memory modification, notably in regard to erasing one’s unwanted memories which are reasonable targets for optogenetic interventions. The first argument concerns the problem of abandoning one’s moral obligations in hypothetical scenarios where the witnesses of a crime wish to erase their memories of the event through optogenetics [15]. While doing so is aligned with one’s right to personal choice if the witnesses find the crime to be far too upsetting to remember, it is not within the interests of society to erase such memories which are useful as testimonies during criminal prosecutions, even if the memories prove to be unreliable. Therefore, it is a moral obligation for witnesses to retain their memories for consequentialist reasons (i.e., preventing future crimes and exploitation) and withholding justice, and the same idea is applicable to the victims of a crime. From the perspective of criminal offenders, furthermore, it is also their moral obligation to retain the memories of their unlawful actions without optogenetic interventions even if they develop a guilty conscience. Otherwise, it would be deemed as an inappropriate moral reaction and responsibility needs to be held nevertheless on the part of the criminal offender if their memories are erased [6, 7].

Retaining memories sustained from traumatic experiences such as discrimination or abuse is also justified in the sense that traumatic memories may have a subtle influence on cultivating one’s personality and values [6]. Children who experienced childhood trauma are found to exhibit elevated levels of empathy as adults relative to children who did not have such experiences, as shown by Greenberg et al. [16]. In turn, having undergone traumatic experiences will ultimately motivate affected individuals to seek and initiate systemic changes in society by means of activism, for instance, to mitigate the root cause of their experienced trauma [6]. To further justify the means of relying on the traumatic memories of individuals to achieve the ends of society’s welfare in the absence of optogenetic interventions, it ought to be reiterated that without such means, social relations among members of society will remain in an oppressive and unspontaneous condition, such that individuals will not be inured to the sufferings of others but live in a continuous state of mass oblivion [15]. Using optogenetics to erase traumatic memories will thus nullify the motivational impulses and humaneness that are shared among affected individuals and most significantly, it has the potential to distort the trajectory of one's personality and values to a certain extent, especially when the valence of the memories is significantly altered to affect one’s dispositions [6].

Traumatic experiences are also pivotal in partially formulating self-defining memories that are of equal importance, for they are the underlying constituents of a person’s fundamental character and their sense of self. This is reinforced by the ideas of John Locke on memory with support from contemporary empirical evidence in spite of critical objections that claim no relationships between memory and personal identity [17]. While dissenting views ought to be acknowledged, the premise of Lockean ideas and any experimental support acts as a vital presumption in the current argument, which asserts that erasing one’s self-defining memories may change an individual’s narrative identity—the integration of one’s internalized, evolving life stories to render the person’s life with unity and meaning [18]. For the reason that narrative identities are malleable to change in sync with individuals’ memories, this implies that the reactivation of previously erased self-defining memories or implanting false memories may fail to be reintegrated with the self [6]. In such circumstances, individuals become susceptible to betraying or self-deceiving their original self as their life deviates from their truthful identity in the event of having their memories manipulated by optogenetics [6].

Analyzing the effects of memory modification on personal identity further requires a discussion on the threat posed toward individual authenticity. While the idea of authenticity has multiple conceptualizations, it is beneficial to consider authenticity from a dual-basis framework that combines accounts from existentialism (self-creation) and essentialism (self-discovery) in prompting critical ethical inquiries regarding the use of optogenetics [6]. Existentialists outline authenticity as having the ability to act upon one’s honest choices and identity without the influence of external social pressure and norms, while essentialists add in the concomitant aspect of being faithful to one’s true self—meaning that the individual has a clear and accurate depiction of their own life narratives in both the past and present that culminated in who they are to drive their purpose in life upon realization. The interference of optogenetics in modifying individuals’ memories suggests the alteration of one’s identity and certain affiliated values, beliefs, and other characteristics. Ultimately, doing so leads to the consequences as described above as one’s authenticity and intrinsic character becomes prone to diminishment and misrepresentation, respectively, thus leading the acts of self-creation and self-discovery into disarray [19, 20].

Note that the act of becoming inauthentic is generally deemed as morally permissible, however, under the circumstance that the choice of undergoing optogenetic intervention to modify one’s memory is made without ambivalence but rather it is derived from one’s higher-order desires that may lead to greater benefits relative to the potential harms, such as PTSD patients with severe symptoms in which conventional treatment methods are ineffective. These cases are important to be considered when formulating effective frameworks for regulating the use of optogenetics, yet questions such as to what extent is one’s external freedom compromised or is the essence of the individual resulted from optogenetic memory modification different than their original self are equally noteworthy for ethical examination. As a result, the dynamic and relational narrative construction of individuals’ identities (i.e., discovering oneself and acknowledging one’s identity) becomes subjugated to conformity in the sense that individual choices are no longer established on the basis of adhering to one’s true self; instead, they stem from the altering effects of optogenetic memory modification that violates the pillars of authenticity at the expense of favoring one’s local autonomy over authenticity. One familiar example is for a naturally shy individual to behave in an outgoing manner when interviewing for jobs that prefer extroverted attributes in its applicants [19, 20, 21].

The authenticity argument in relation to one’s identity nevertheless suffers from criticisms regarding the practical utility of the dual-basis framework in assessing memory modification and its implications given the individual-focused and idealistic framing of ideas. Despite everything, the dual-basis framework offers a well-balanced account of the complexity of neuroscience and psychology by presenting both the possibilities and constraints of creating one’s narrative identity [20]. Though interestingly, Kostick and Lázaro-Muñoz have argued that the brain has neural safeguards against inauthenticity caused by optogenetics that relies on neuroplasticity [22]. Of note that the discussion above only entails the worst-case scenarios of memory modification, however, to help guide future directions in the neuroethics of optogenetic applications since the degree of optogenetic effects on memory has yet to be demarcated. Therefore, it is worthwhile to be reliant upon the possible outcomes of hypotheticals to gauge reality, for it is currently difficult to translate optogenetic findings in animal models to humans in conjunction with the lack of a comprehensive neurobiological understanding of memory’s unpredictable nature.

As with any novel neurotechnology with an undefined impact, optogenetics imposes its own risks and benefits for the purpose of memory modification that requires a neuroethical evaluation of its ramifications in changing the properties and dimensions of memory. The arguments that have been presented herein is reminiscent of the events that unfolded in the 2004 romance and science fiction film Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, where the two protagonists both decided to undergo the procedure of having their memories of each other removed following a breakup, only to found remorse in the aftermath as they tried to reconcile their relationship despite the loss of their memories. Therefore, memory is what keeps the stories of our lives in a continuous state of progression as what oxygen is to fire; it is the gate that reveals our identities, values, ambitions, struggles, and relations to one another to empower us to live happily in a dreadful world in remembrance of who we are and those who we cherish.

References

1. Josselyn, S. A. (2018). The past, present and future of light-gated ion channels and optogenetics. Elife, 7, e42367.

2. Felsen, G., & Blumenthal-Barby, J. (2022). 7 Ethical Issues Raised by Recent Developments in Neuroscience: The Case of Optogenetics. Neuroscience and Philosophy.

3. Alberts, B., Johnson, A., Lewis, J., Raff, M., Roberts, K., & Walter, P. (2002). Ion channels and the electrical properties of membranes. In Molecular Biology of the Cell. 4th edition. Garland Science.

4. Fenno, L., Yizhar, O., & Deisseroth, K. (2011). The development and application of optogenetics. Annual review of neuroscience, 34, 389-412.

5. Carter, M., & Shieh, J. C. (2015). Guide to research techniques in neuroscience. Academic Press.

6. Adamczyk, A. K., & Zawadzki, P. (2020). The memory-modifying potential of optogenetics and the need for neuroethics. NanoEthics, 14(3), 207-225. 7. Canli, T. (2015). Neurogenethics: An emerging discipline at the intersection of ethics, neuroscience, and genomics. Applied & translational genomics, 5, 18-22. 8. Hamilton, G. F., & Rhodes, J. S. (2015). Exercise regulation of cognitive function and neuroplasticity in the healthy and diseased brain. Progress in molecular biology and translational science, 135, 381-406.

9. Liu, X., Ramirez, S., & Tonegawa, S. (2014). Inception of a false memory by optogenetic manipulation of a hippocampal memory engram. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 369(1633), 20130142.

10. Guskjolen, A., Kenney, J. W., de la Parra, J., Yeung, B. R. A., Josselyn, S. A., & Frankland, P. W. (2018). Recovery of “lost” infant memories in mice. Current Biology, 28(14), 2283-2290.

11. Rook, N., Tuff, J. M., Isparta, S., Masseck, O. A., Herlitze, S., Güntürkün, O., & Pusch, R. (2021). AAV1 is the optimal viral vector for optogenetic experiments in pigeons (Columba livia). Communications Biology, 4(1), 100.

12. Chen, R., Gore, F., Nguyen, Q. A., Ramakrishnan, C., Patel, S., Kim, S. H., ... & Deisseroth, K. (2021). Deep brain optogenetics without intracranial surgery. Nature biotechnology, 39(2), 161-164.

13. Lin, J. Y., Knutsen, P. M., Muller, A., Kleinfeld, D., & Tsien, R. Y. (2013). ReaChR: a red-shifted variant of channelrhodopsin enables deep transcranial optogenetic excitation. Nature neuroscience, 16(10), 1499-1508.

14. Andrei, A. R., Debes, S., Chelaru, M., Liu, X., Rodarte, E., Spudich, J. L., ... & Dragoi, V. (2021). Heterogeneous side effects of cortical inactivation in behaving animals. Elife, 10, e66400.

15. Kolber, A. J. (2006). Therapeutic forgetting: The legal and ethical implications of memory dampening. Vand. L. Rev., 59, 1559.

16. Greenberg, D. M., Baron-Cohen, S., Rosenberg, N., Fonagy, P., & Rentfrow, P. J. (2018). Elevated empathy in adults following childhood trauma. PLoS one, 13(10), e0203886.

17. Robillard, J. M., & Illes, J. (2016). Manipulating memories: The ethics of yesterday’s science fiction and today’s reality. AMA Journal of Ethics, 18(12), 1225-1231.

18. McAdams, D. P., & McLean, K. C. (2013). Narrative identity. Current directions in psychological science, 22(3), 233-238.

19. Tan, S. Z. K., & Lim, L. W. (2020). A practical approach to the ethical use of memory modulating technologies. BMC Medical Ethics, 21(1), 1-14. 20. Leuenberger, M. (2022). Memory modification and authenticity: a narrative approach. Neuroethics, 15(1), 10.

21. Zawadzki, P. (2023). The Ethics of Memory Modification: Personal Narratives, Relational Selves and Autonomy. Neuroethics, 16(1), 6.

22. Kostick, K. M., & Lázaro-Muñoz, G. (2021). Neural safeguards against global impacts of memory modification on identity: ethical and practical considerations. AJOB neuroscience, 12(1), 45-48.