There is a difference between morals and ethics. Too often they are used interchangeably especially in the context of medical decisions. Morals are defined by an individual’s principles regarding right and wrong whereas ethics are determined by an external source.1 The ability to separate morals from ethics while consulting with patients can be difficult at times, but necessary. Recently, a friend confided in me about a medical situation occurring within her family. She asked for my thoughts and a recommendation. Initially, I let my emotions and my moral beliefs rule and offered my thoughts. After a while, I revisited the issue and realized my morals overruled ethics.

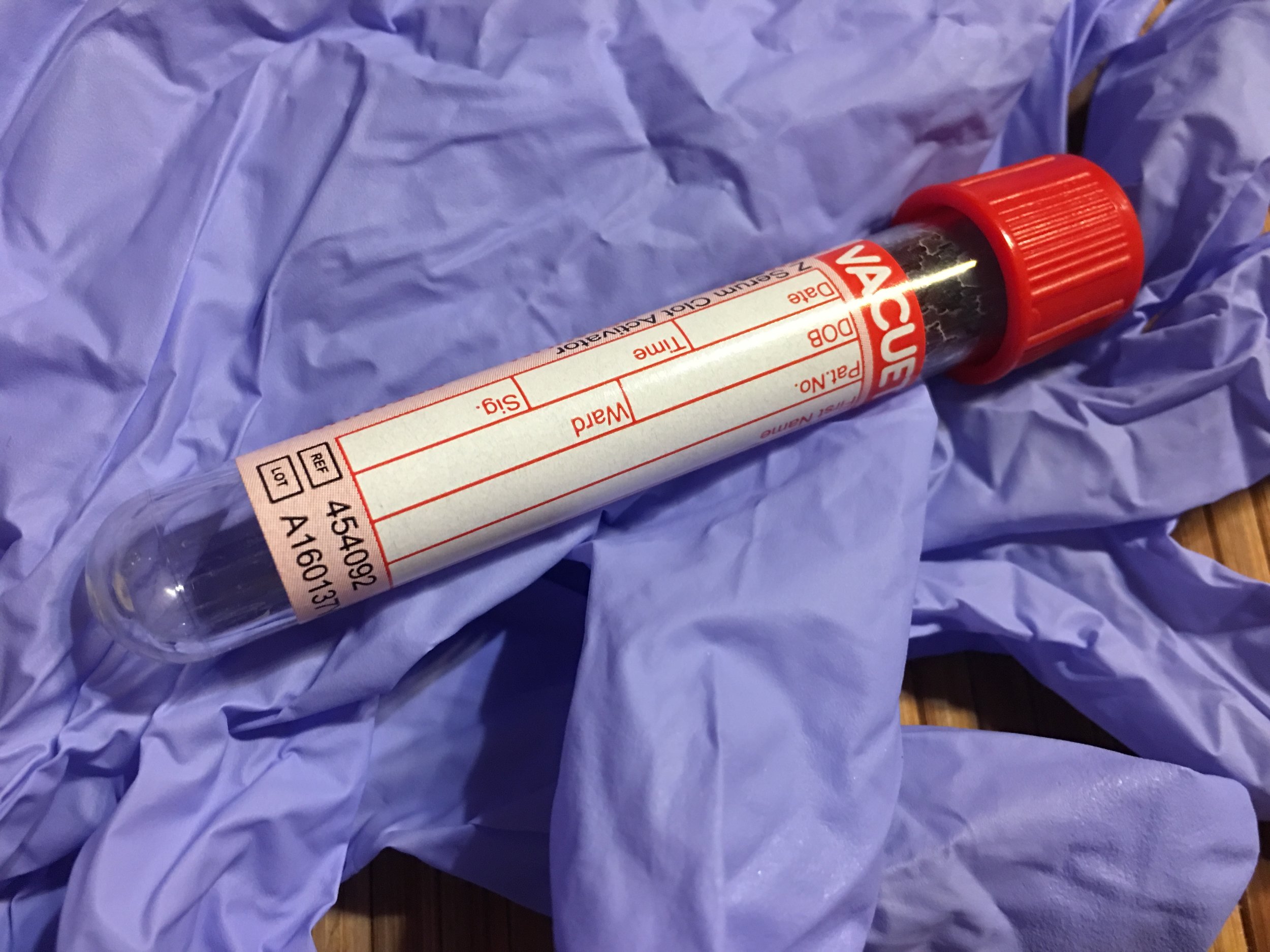

The case brought to me involved organ donation and the desire to have a family member submit to compatibility testing. Compatibility testing is also known as cross-matching. Compatibility testing is

“ a procedure vital in blood transfusions and organ transplantation. The recipient’s erythrocytes ( a red blood cell or corpuscle; one of the formal elements in the peripheral blood. Normally, in the human, mature erythrocytes are biconcave disks that have no nuclei. Erythrocyte formation takes place in the red bone marrow in the adult, and in the liver, spleen, and bone marrow of the fetus) or leukocytes ( a colorless cell, white blood cell, that circulates in the blood and other bodily fluids are incubated with the donor’s serum and vice versa. Various testing procedures are then performed to insure that the donor and recipient are blood group compatible or histocompatible (compatibility between the tissues of donor and recipient, ensuring the donor accepts the transplant or transfusion without having an immune reaction.).2

She desired to know if the member had an obligation to undergo testing. Morally, I believed the family member had a duty to agree to test. I was taken aback by the refusal to go through with testing and the further refusal to donate if needed. With a clear conscience, how could one refuse to help a family member? Basing a decision on my conscience was improper. My friend’s case was not a case study to be analyzed. My conscience would not refuse to test for compatibility, but not everyone shares my conscience or my morals. I had to go back to my friend and change my initial recommendation because, in this case, ethics overruled morals. When an ethical dilemma presents itself in the healthcare setting, there are ethical codes of conduct to be considered before making a recommendation. It is my responsibility to include laws regarding compatibility testing. The question I need to ask is: Is it ethically correct to force another to test for compatibility for any illness?

The law cannot be coercive in this respect. Any legislation requiring that all blood relatives of a person with any life-threatening illness affecting the well-being of the patient must undergo testing. Based on that testing if the relative is a match, he/she will be required to consent to be a donor. In McFall v. Shimp, it is acknowledged that the common law has consistently held to a rule which provides that one human being is under no legal compulsion to give aid or to take action to save another human being or to rescue. The court felt that this rule defines the “very essence of our free society.”3 In McFall v. Shimp, the majority stated that “to force one to donate would be to violate our first principle which is

“the respect for the individual, and that society and government exist to protect the individual from being invaded and hurt by another.” The authors continue,” For a society which respects the rights of one individual, to sink its teeth into the jugular vein or neck of one of its members and suck from it sustenance for another member, is revolting to our hard-wrought concepts of jurisprudence.”3

My friend’s case is not an example of interdependence as in Strunk v. Strunk.4 One person will not physically die while the other emotionally fades if an organ or bone marrow is not given. My friend’s family member's life or emotional well-being was not dependent upon the family member testing for compatibility. He could ask others to test for compatibility or be placed on the waitlist for an organ.

After returning to her case and explaining my change, I thought again about the need to put morals and ethics in separate boxes when making medical recommendations. I figured I was immune to letting my morals be my guide, but I wasn’t. Further reflection and an assessment of the ethics surrounding the case was needed to make a recommendation correctly. None of us are infallible, we let our hearts lead us sometimes, but the need to lead with my head and not my heart is critical especially when asked by friends to make recommendations regarding the well-being of others.

References

Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed September 24, 2017, https://www.britannica.com/demystified/whats-the-difference-between-morality-and-ethics

Encyclopedia and Dictionary of Medicine, Nursing, and Allied Health, 7th ed.,”cross matching.”

McFall v. Shimp,10 Pa.D&C 3d90(1978).

Strunk v. Strunk, 445 S.W.2d145 (Ky. 1969).